While my kids may be avid readers, they are obsessive artists, and they don't need any coaxing to whip out the paper and pencils. Observational drawing, interpretive drawing, representational drawing - you name it, they're doing it. Here are some of their recent works:

1. Rhyming and drawing: Violet is a huge fan of Jim Aylesworth, and we currently have his The Cat and the Fiddle and More checked out of the library. One afternoon while Sy and I were out and about, she wrote her own rhyme:

Hey Ducka Ducka

The rabbit drove a trucka,

The dog learned to jump real high,

The little pig laughed to see such sport

And the spider ran away with the fly.

Then she illustrated her rhyme:

2. Drawing what you hear: we always have music one for the kids (though you won't catch The Wiggles anywhere near our stereo) and one day Jason suggested to Sy that he draw everything he heard while listening to an album by Emeralds. After about 20 minutes, Sy showed him this:

Not only did he draw the drummer, keyboardist, violinist, guitarist and "the guy making that beeping sound," but he drew them from different positions (both side and front) - this was a first, and I was totally amazed!

3. Observational drawing: this is by far the hardest! How do you paint the "whippy parts of the wind" or the gases surrounding the planets? Here is Sy's pencil drawing of the Ring Nebula, which he drew while looking at a photo from one of his space books:

4. Creative/improvisational drawing: these are my favorites. While some of them are representational, they aren't your run of the mill representations. Sy's clown is probably the easiest to "read" for the viewer:

In case you didn't notice, his hands are behind his back.

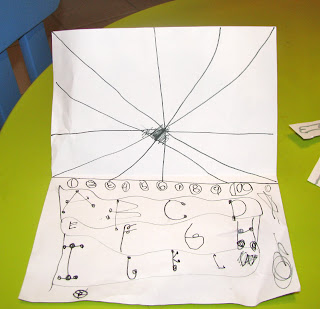

Sy's most recent "mass product" is the laptop, complete with "an ocean of letters":

But then there is Violet's lion:

Sy's crying monster:

Violet's picture of "Mommy and Invisible Sy" (that's him on the right):

And finally, Violet's "faces":

I am pretty convinced at this point that she will either be a visual or a circus artist - this stuff really blows me away.